By Lucinda Glover, with contributions from Michael Woods, London School of Economics

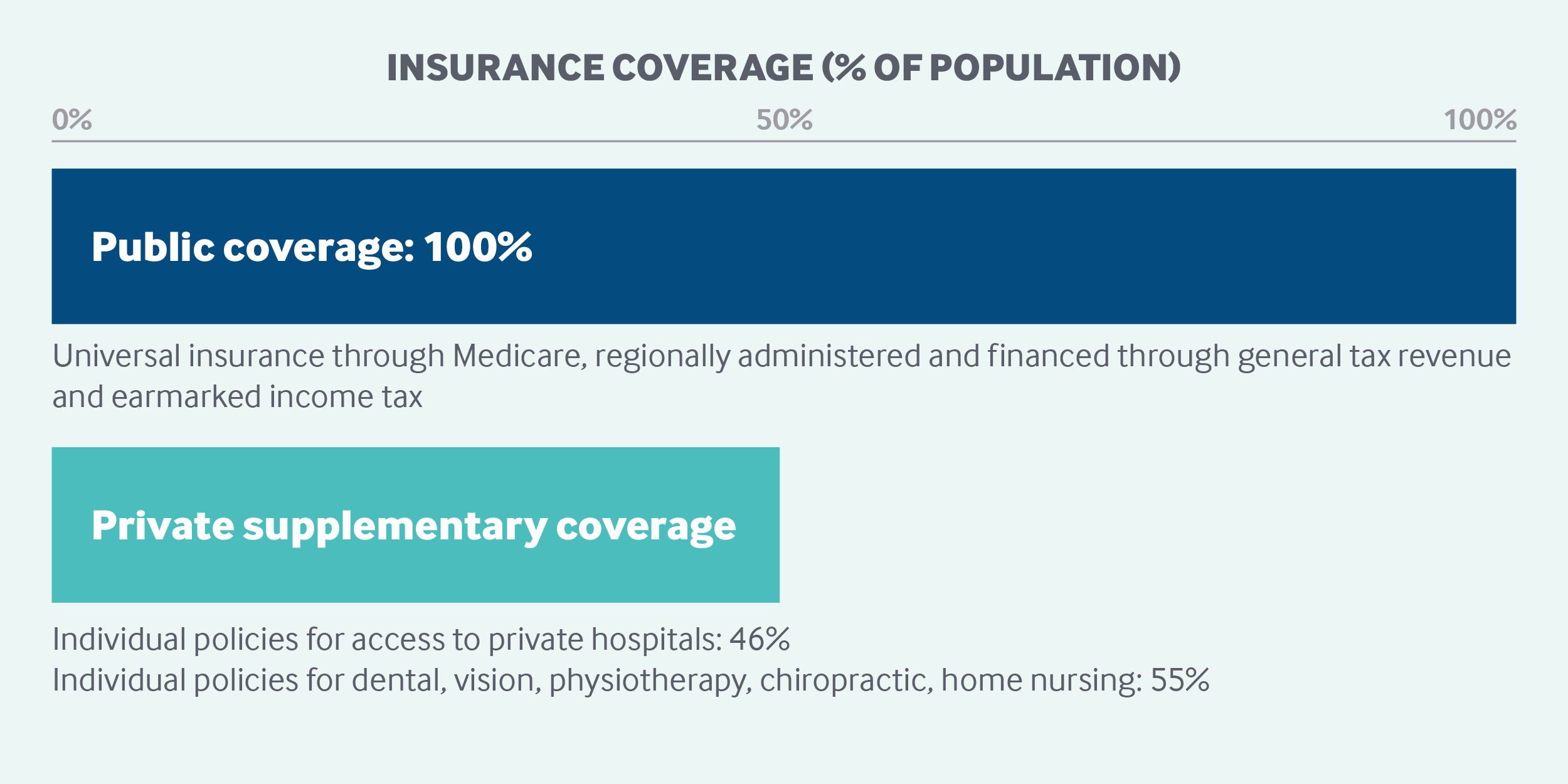

Australia has a regionally administered, universal public health insurance program (Medicare) that is financed through general tax revenue and a government levy. Enrollment is automatic for citizens, who receive free public hospital care and substantial coverage for physician services, pharmaceuticals, and certain other services. New Zealand citizens, permanent residents, and people from countries with reciprocal benefits are eligible to enroll in Medicare. Approximately half of Australians buy private supplementary insurance to pay for private hospital care, dental services, and other services. The federal government pays a rebate toward this premium and also charges a tax penalty on higher-income households that do not purchase private insurance.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

It took 10 years of political tension to establish Australia’s universal public health insurance program, known as Medicare.

A universal health care bill was initially introduced in Parliament in 1973 but failed three times to pass through the Senate. Because of these failed attempts, a new parliamentary election was called, a procedure known as double dissolution, to resolve the deadlock. The new Parliament passed the health care legislation in 1974, establishing free public hospital care and subsidized private care. However, following a change in government in 1975, access to free health care services was limited to retired persons who met stringent means tests.

After another change of government in 1984, the current Medicare system was established. Medicare provides free public hospital care and substantial coverage for physician services and pharmaceuticals for Australian citizens, residents with permanent visas, and New Zealand citizens following their enrollment in the program and confirmation of identity.1 Restricted access is provided to citizens of certain other countries through formal agreements.2 Other visitors to Australia, as well as undocumented immigrants, do not have access to Medicare and are treated as private-pay patients, including those needing emergency services.

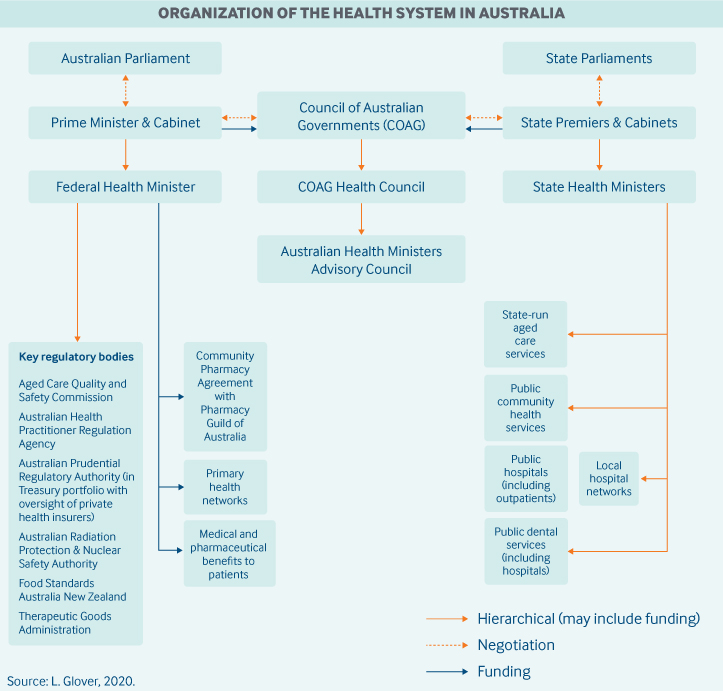

Role of government: Three levels of government are collectively responsible for providing universal health care:

The federal government provides funding and indirect support for inpatient and outpatient care through the Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) and for outpatient prescription medicine through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The federal government is also responsible for regulating private health insurance, pharmaceuticals, and therapeutic goods; however, it has a limited role in direct service delivery.

States own and manage service delivery for public hospitals, ambulances, public dental care, community health (primary and preventive care), and mental health care. They contribute their own funding in addition to that provided by federal government. States are also responsible for regulating private hospitals, the location of pharmacies, and the health care workforce.

Local governments play a role in the delivery of community health and preventive health programs, such as immunizations and the regulation of food standards.3

At the federal level, intergovernmental collaboration and decision-making occur through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), with representation from the prime minister and the first ministers of each state. The COAG focuses on the highest-priority issues, such as major funding discussions and the interchange of roles and responsibilities among governments. The COAG Health Council is responsible for more detailed policy issues and is supported by the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council.

The federal Department of Health oversees national policies and programs, including the MBS and PBS. Payments through these schemes are administered by the Department of Human Services.

Other federal agencies involved in health care include the following:

- The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee provides advice to the Minister for Health on the cost-effectiveness of new pharmaceuticals (but not routinely on delisting).

- The Australian Digital Health Agency is responsible for matters relating to electronic health data, and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) also provide health data.

- The Therapeutic Goods Administration oversees supply, imports, exports, manufacturing, medical devices, pharmaceutical safety, and advertisement.

- The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency ensures registration and accreditation of the workforce in partnership with national boards.

- The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority regulates private health insurance, and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission promotes competition among private health insurers.

The state governments operate their own departments of health and have delegated the management of hospitals to Local Hospital Networks. These hospital networks are responsible for working collaboratively with federally funded Primary Health Networks, which were established in 2015 to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and coordination of care. Primary Health Networks have boards comprising medical professionals and community advisory committees.

Role of public health insurance: Total health expenditures in 2015–2016 represented 10.3 percent of the GDP, an increase of 3.6 percent from 2014–2015. Two-thirds of these expenditures (67%) were funded by the government.4

Medicare is funded through the national tax system, in part by a government levy, which raised an estimated AUD 114.6 billion (USD 80.14 billion)5 in 2015–2016.6 Since 2014, a share of the money raised from this levy also supports the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

Role of private health insurance: Private health insurance is readily available and offers coverage for out-of-pocket fees and private providers, greater choice of providers (particularly in hospitals), faster access to nonemergency services, and rebates for selected services. Private health insurance may include coverage for hospital care, general treatment, or ambulance services. General treatment coverage provides insurance for dental, physiotherapy, chiropractic, podiatry, home nursing, and optometry services. Coverage may be capped by dollar amount or by number of services. For hospital services, patients can opt to be treated as a public patient (with full fee coverage) or as a private patient (with 75% fee coverage).

Government policies encourage enrollment in private health insurance through a tax rebate (8.5%–33.9%, depending on age and income) and an income-based penalty payment (1%–1.5%) for not having private insurance. This penalty, known as the Medicare Levy surcharge, applies only to singles with incomes above $90,000 and families with incomes above $180,000.7

The Lifetime Health Coverage program provides a lower health insurance premium for life. However, there is a 2 percent increase in the base premium for each year after age 30. Consequently, sign-up is highest among those 30 and under, with a trend to opt out starting at age 50.

Nearly half of the Australian population (46%) had private hospital coverage and nearly 55 percent had private general treatment coverage in 2016.8 However, coverage varies by socioeconomic status: Private health insurance covers just one in five (22%) of the most disadvantaged 20 percent of the population, but more than 57 percent of the most advantaged population quintile. This disparity is due, in part, to the Medicare Levy surcharge applied to higher-income earners.9

Insurers are a mix of for-profit and nonprofit providers. In 2015–2016, private health insurance expenditures represented 8.8 percent of all health spending.10

Services covered: The federal government defines and funds MBS benefits, which cover hospital care and medical services, including mental health and maternity care. MBS also provides for limited optometry and children’s dental care.

Pharmaceutical subsidies are provided by the government through the PBS. To be listed, pharmaceuticals need to be approved for cost-effectiveness by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee.

The federal government also funds cancer screening and immunization programs that are provided free to targeted population groups.

States are responsible for the delivery of free public hospital services, preventive care, chronic disease management, and supplementary mental health care not covered by Medicare. States also provide means-tested access to medical equipment such as wheelchairs.

Home care for the elderly and hospice care coverage are funded separately by Medicare (see “Long-term care and social supports,” below).

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: Out-of-pocket payments accounted for 16.5 percent of total health expenditures in 2016–2017. The largest share (68%) was for primary care, of which one-third (37%) was for medications, followed by hospital care (11%).11

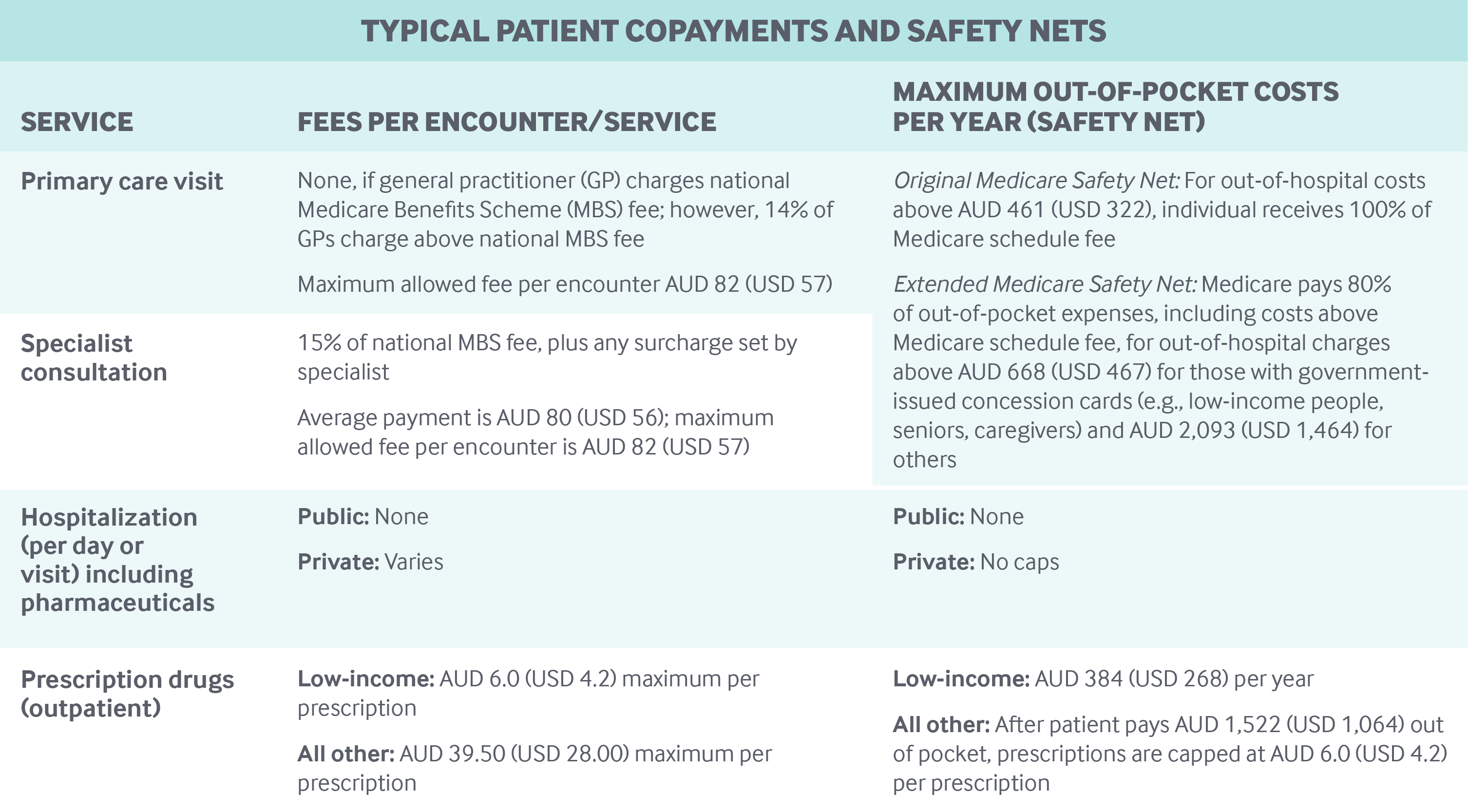

Under Medicare, there are no deductibles or out-of-pocket costs for public patients receiving public hospital services. Cost-sharing for outpatient care varies. The federal government sets Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) fees for general practitioner (GP) and specialty visits; it pays GPs 100 percent of the fee and specialists 85 percent. Patients pay the remaining 15 percent of specialist fees, as well as any surcharges. GPs and specialists can choose to charge above the MBS fees, although there is a maximum patient out-of-pocket fee of AUD 83.40 (USD 57.00) per service. About 86 percent of GP visits were provided without an additional charge to patients in 2016–2017.12 Patients who were charged paid an average of AUD 31 (USD 22).

Out-of-pocket outpatient pharmaceutical expenditures are capped under the PBS (see table). Consumers pay the full price of medicines not listed on the PBS. Pharmaceuticals provided to inpatients in public hospitals are generally free.

Safety nets: In addition to providing free public hospital care and capped drug costs, Australia has three safety nets to help with other out-of-pocket costs:

- The Original Medicare Safety Net covers the MBS fee for all out-of-hospital Medicare services above an annual out-of-pocket threshold of AUD 461 (USD 322). If there are charges above the fee, the individual is responsible for them.

- The Extended Medicare Safety Net covers 80 percent of out-of-pocket, out-of-hospital costs (these include costs above the MBS fee) over an annual threshold of AUD 668 (USD 467) for those with government-issued concession cards (e.g., low-income people, seniors, caregivers) and AUD 2,093 (USD 1,464) for others.

A maximum out-of-pocket fee per out-of-hospital service (known as the Greatest Permissible Gap) is set at AUD 83.40 (USD 57.00); this fee may be covered by private health insurance for those with coverage.13 War veterans, the widowed, and their dependents may be eligible for further discounts.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Physicians are trained primarily at public (but also private) universities, with their fees subsidized through the tax system. Annual tuition fees are approximately AUD 65,000 (USD 45,454), with the student contribution capped at AUD 10,754 (USD 7,520) per annum for Australian citizens.15

The federal government provides primary care doctors with financial incentives to practice in rural and remote areas. There is no cap on the number of physicians in Australia, and workforce shortages are addressed through internationally trained providers.

Primary care: In 2015, there were 34,367 GPs, 49,060 practitioners registered as both generalists and specialists, and 8,386 providers registered as specialists.16 GPs are typically self-employed, with about four physicians per practice on average.17 In 2013–2014, GPs earned an average of AUD 3,024 (USD 2,115) per week, around half (56%) of what specialists earned.18 The schedule of MBS service fees is set by the federal health minister. Registration with a GP is not required, and patients choose their primary care doctor. GPs operate as gatekeepers; a referral to a specialist is needed for a patient to receive the MBS subsidy for specialist services.

GPs are paid primarily on a fee-for-service basis through the MBS model, although they can also receive funding from a performance-based initiative called the Practice Incentives Program. The Practice Incentives Program accounts for 5.5 percent of federal expenditures on GPs.19

The federal government also encourages multidisciplinary care coordination by funding large multidisciplinary GP clinics, known as Super Clinics, and through the establishment of Primary Health Networks, which support more efficient, effective, and coordinated primary care.

In 2015, there were 11,040 nurses or midwives working in a general practice setting.20 Their role has been expanding with the addition of a practice nurse payment in the Practice Incentives Program. Nurses in general practice settings provide chronic disease management and care coordination, preventive health education, and oversight of patient follow-up and reminder systems.

Outpatient specialist care: Specialists deliver outpatient care in private practice (8,001 specialists in 2015) or in public hospitals (3,745).21 Patients are able to choose which specialist they see but must be referred by their GP to receive MBS subsidies. Specialists are paid on a fee-for-service basis. They receive federal subsidies for 85 percent of the MBS fee and set their patients’ out-of-pocket fees independently. Many specialists split their time between private and public practice.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Many practices have the technology to process claims electronically so that reimbursements from public and private payers are instantaneous, and patients pay only their copayment (if the provider charges above the MBS fee). If the technology is not in place, patients pay the full fee and seek reimbursement from Medicare and/or their private insurer.

After-hours care: GPs are required to ensure that after-hours care is available to patients, but are not required to provide care directly. They must demonstrate that processes are in place for patients to obtain information about after-hours care and that patients can contact them in an emergency. After-hours walk-in services are available and may be provided in a primary care setting or within hospitals. Because there is free access to emergency departments, some patients may use these facilities for after-hours primary care.

The government also provides funds to Primary Health Networks to support and coordinate after-hours services, and there is an after-hours advice and support line.

Hospitals: In 2016–2017, there were 695 public hospitals (673 acute, 22 psychiatric), with a total of nearly 60,300 beds. Hospital beds have increased by an annual average of 1.5 percent, maintaining a consistent supply of 2.5 beds per 10,000 population. In the same period, there were 630 private hospitals (341 day hospitals and 289 others) with 33,100 beds.22 Private hospitals are a mix of for-profit and nonprofit.

Public hospitals receive a majority of funding (92%) from the federal government and state governments, with the remainder coming from private patients and their insurers. Most of the public hospital funding (66% of total recurrent expenditures) goes toward the salaries of employed physicians.

Private hospitals receive most of their funding from private health insurers and patients (68%), with 32 percent coming from government.23

Public hospitals are organized into Local Hospital Networks, of which there were 136 in 2016–2017. These vary in size, depending on the population they serve and the extent to which linking services and specialties on a regional basis is beneficial. In major urban areas, a number of Local Hospital Networks comprise just one hospital.

State governments fund their public hospitals largely on an activity basis, using diagnosis-related groups. Federal funding for public hospitals includes a base amount plus money for growth (for further details, see “How are costs contained?”).

Small rural hospitals are funded through block grants.24

Pharmaceuticals used in hospitals are subsidized by the federal government through the PBS.

Mental health care: Mental health services are a responsibility shared by the federal and state governments as articulated through a rolling series of five-year National Mental Health Plans, with the current plan running until 2022. In addition, federal and state health ministers agreed to the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan in August 2017.

Mental health care is provided in many settings, including GPs and specialist care, community-based care, hospitals (both inpatient and outpatient, public and private), and residential care. GPs provide general mental health care and may devise treatment plans of their own or refer patients to specialists. Specialist care and pharmaceuticals are subsidized through the MBS and PBS.

State governments fund and deliver acute mental health and psychiatric care in hospitals, community-based services, and specialized residential care. Public hospital–based care is free to public patients.

In addition, nonprofit organizations, such as LifeLine, BeyondBlue, and HeadSpace, provide important services ranging from suicide prevention to primary preventive care for both adults and youth.

Australia spent AUD 9.0 billion on mental health–related services in 2015–2016. Most of this expenditure goes toward services delivered by state governments ($5.4 billion), with AUD 2.4 billion being for public hospital services and $2.0 billion for community health services. The Australian government subsidizes additional mental health services through the MBS (AUD 1.2 billion) and the PBS (AUD 511 million). Specialized mental health services in private hospitals cost AUD 493 million in 2015–2016.25

Long-term care and social supports: Three out of four people receiving long-term care receive residential aged care (nursing home care). Three-quarters of older Australians receive informal care and 60 percent receive formal care. In 2015, 11 percent of Australians were informal caregivers, and 32 percent of these caregivers were the primary caregiver, or carer.

In 2011–2012, the federal government provided AUD 3.18 billion (USD 2.22 billion) under the income-tested Carer Payment program for caregivers who are providing constant care and are unable to be otherwise employed. The government also contributes AUD 1.75 billion (USD 1.22 billion) to a separate caregiver program, called the Carer Allowance, that provides a supplement for daily care to primary carers, regardless of their income. In addition, the federal government provides an annual Carer Supplement of AUD 480 million (USD 336 million) to help with the cost of caring. Recipients of the Carer Allowance who care for a child under the age of 16 receive an annual Child Disability Assistance Payment of AUD 1,000 (USD 699). There are also a number of respite programs providing further support for caregivers.26

Home care for the elderly is provided through the Commonwealth Home Support Program in all states except Western Australia. Subsidies are income-tested and may require copayments from recipients. Services can include assistance with housework, basic care, physical activity, and nursing, among others. The program began in July 2015 and combines home and community care, respite care for caregivers, day therapy, and assistance with care and housing.27 The Western Australian government has its own initiative, the Home and Community Care Program, which is delivered with funding support from federal government.

Residential aged care be private nonprofit, for-profit, or run by state or local governments. Federally subsidized nursing home accommodations are available. The Australian government supports both permanent and respite residential care. Eligibility is determined through a needs assessment, and permanent care and accommodation costs are means-tested.28

Hospice care is provided by states through complementary programs funded by the Commonwealth.

In 2013, the federal government, in partnership with states, implemented the pilot phase of the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Full implementation is planned by 2020, at which point around 460,000 Australians are expected to receive support.29 The scheme provides more flexible funding support for long-term care (not means-tested), to allow greater tailoring of services. The main component of the NDIS is individualized packages of support to eligible people with disabilities.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

The overarching strategy for ensuring quality of care is captured in the National Healthcare Agreement of the COAG (2012). The agreement sets out the common objective of Australian governments in providing health care — a sustainable system with improved outcomes for all — and the performance indicators and benchmarks on which progress is assessed. It also sets out national-priority policy directions, programs, and areas for reform, such as addressing major chronic diseases and their risk factors. Indicators and benchmarks in the agreement address issues of quality from primary to tertiary care and include disease-specific targets of high priority, as well as general benchmarks.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) is the main body responsible for safety and quality improvement in health care. The ACSQH has developed service standards that have been endorsed by health ministers. These include standards for conducting patient surveys, which must be met by hospitals and day surgery centers to ensure accreditation. The Australian Bureau of Statistics, the national government statistical body, also undertakes an annual patient experience survey.

The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards is the (nongovernment) agency authorized to accredit provider institutions. States license and register private hospitals and the health workforce, legislate on the operation of public hospitals, and work collaboratively through the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme to facilitate workforce mobility across jurisdictions while maintaining patient protections. States also ensure that the workforce maintains minimum hours and standards of continuing education to maintain accreditation.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has responsibility for accrediting GPs. To be eligible for government subsidies, aged-care services must be accredited by the government-owned Aged Care Standards and Accreditation Agency. Beginning in January 2019, the new Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission will be responsible for regulation, compliance, and complaints for aged care.

There are a number of disease and device registries. Government-funded registries are housed in universities and nongovernmental organizations, as well as within state governments. The ACSQH has developed a national framework to support consistent registries.

The National Health Performance Authority reports on the comparable performance of Local Hospital Networks, public and private hospitals, and other key health service providers, but not nursing homes or home care agencies. The reporting framework, agreed to by the Council of Australian Governments, includes measures of equity, effectiveness, and efficiency.

The federal government has regulatory oversight of quarantine, blood supply, pharmaceuticals, and therapeutic goods and appliances.30 In addition, there are a number of national bodies that promote quality and safety of care through evidence-based clinical guidelines and best-practice advice. They include the National Health and Medical Research Council and Cancer Australia.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

The most prominent disparities in health outcomes are between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population and the rest of Australia’s population; these are widely acknowledged as unacceptable. In 2008, the COAG agreed to set a target for closing the gap in life expectancy by 2031. This is a government and nongovernment effort, with the nongovernment component supported through the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Progress toward this target is not on track, with the gap currently at 10.6 years for males and 9.5 for females. From 2005–2007 to 2010–2012, there was a very small reduction in the gap of 0.8 years for males and 0.1 years for females.31

Disparities between major urban centers and rural and remote regions, and across socioeconomic groups, are also major challenges. The federal government provides financial incentives to encourage GPs and other health workers to work in rural and remote areas, where it can be very difficult to attract a sufficient number of practitioners. This challenge is also addressed, to an extent, through the use of telemedicine.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

Approaches to improving integration and care coordination include the Practice Incentives Program, which provides a financial incentive to providers for the development of care plans for patients with certain conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, and mental health needs.

In addition, the Primary Health Networks were established in July 2015 with the objective of improving coordinated care, as well as the efficiency and effectiveness of care for those at risk of poor health outcomes. These networks are funded through grants from the federal government and will work directly with primary care providers, health care specialists, and Local Hospital Networks. Care also may be coordinated by Aboriginal health and community health services.

What is the status of electronic health records?

The Australian Digital Health Agency, established in July 2016, has national responsibility for the country’s digital health strategy. An interoperable national e-health program based on personally controlled unique identifiers is now in operation. More than 6 million patients (one-quarter of Australians) and 13.4 million providers are currently registered. As of February 2019, all Australians have a My Health Record created for them unless they have opted out of the system, although individuals can choose to delete their record at any time.32 The record supports prescription information, medical notes, referrals, and diagnostic imaging reports. Patients can view their own medical information and control who can see it, as well as add information about allergies, adverse reactions, and their health care wishes in the event that they become unable to communicate.

How are costs contained?

The major drivers of cost growth are the MBS and PBS. The federal government regularly considers opportunities to reduce spending growth in the MBS through its annual budget process. To influence PBS costs, the government makes determinations about which pharmaceuticals to list on the scheme and negotiates the price with suppliers. It also provides funds to pharmacies to dispense medicines subsidized through the PBS and to support professional programs and the wholesale supply of medicines. This arrangement is implemented through the current Community Pharmacy Agreements, which are renegotiated every five years. The Sixth Community Pharmacy Agreement, which began in July 2015, supports AUD 6.6 billion (USD 4.6 billion) in savings through supply chain efficiencies.33

Hospital budgets are set by the Local Hospital Networks. Hospitals are funded on the basis of what is determined to be an efficient price for delivering services, as determined by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. Through 2020, the Commonwealth will fund 45 percent of the efficient growth in these services, capped at 6.5 percent of total growth.34 States are required to cover the remaining cost of services, providing an incentive to keep costs at the efficient price or lower.

Beyond these measures, health costs are controlled mainly through capacity constraints, such as workforce supply.

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

The Australian government has introduced a number of reforms to care for older people aimed at improving financial sustainability, quality, and consumer choices. The independent Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, established in early 2019, will bring together previously disparate functions of quality assurance, complaints, and regulation of the aged care sector. The government has also started conducting unannounced audits of aged-care (or nursing) homes for reaccreditation.

The Australian government is also investing more funding to help people remain in their own homes as they age. One example is the Community Visitor scheme, which supports the 70 percent of elderly people who receive aged care at home and experience loneliness.

In its 2018 budget, the federal government allocated AUD 102.5 million (USD 71.7 million) to services for older Australians, with AUD 82.5 million (USD 57.7 million) for residents of aged-care facilities and AUD 20.0 million (USD 14.0 million) for those in the community at risk of isolation.

The 2018 budget also included AUD 72.6 million (USD 50.8 million) for suicide prevention and follow-up care for the adult population and AUD 110 million (USD 77 million) for child and youth health care.

In 2017, the Australian government launched Head to Health, a one-stop electronic resource to direct people experiencing mental health issues to services and resources, supporting them in taking control of their health by reaching out to high-quality, reputable providers. The website was developed in partnership with people and families who have experienced a mental health issue, as well as those who provide care.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of LSE research assistant Michael Woods.