By Sara Allin, Greg Marchildon, and Allie Peckham, North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, University of Toronto

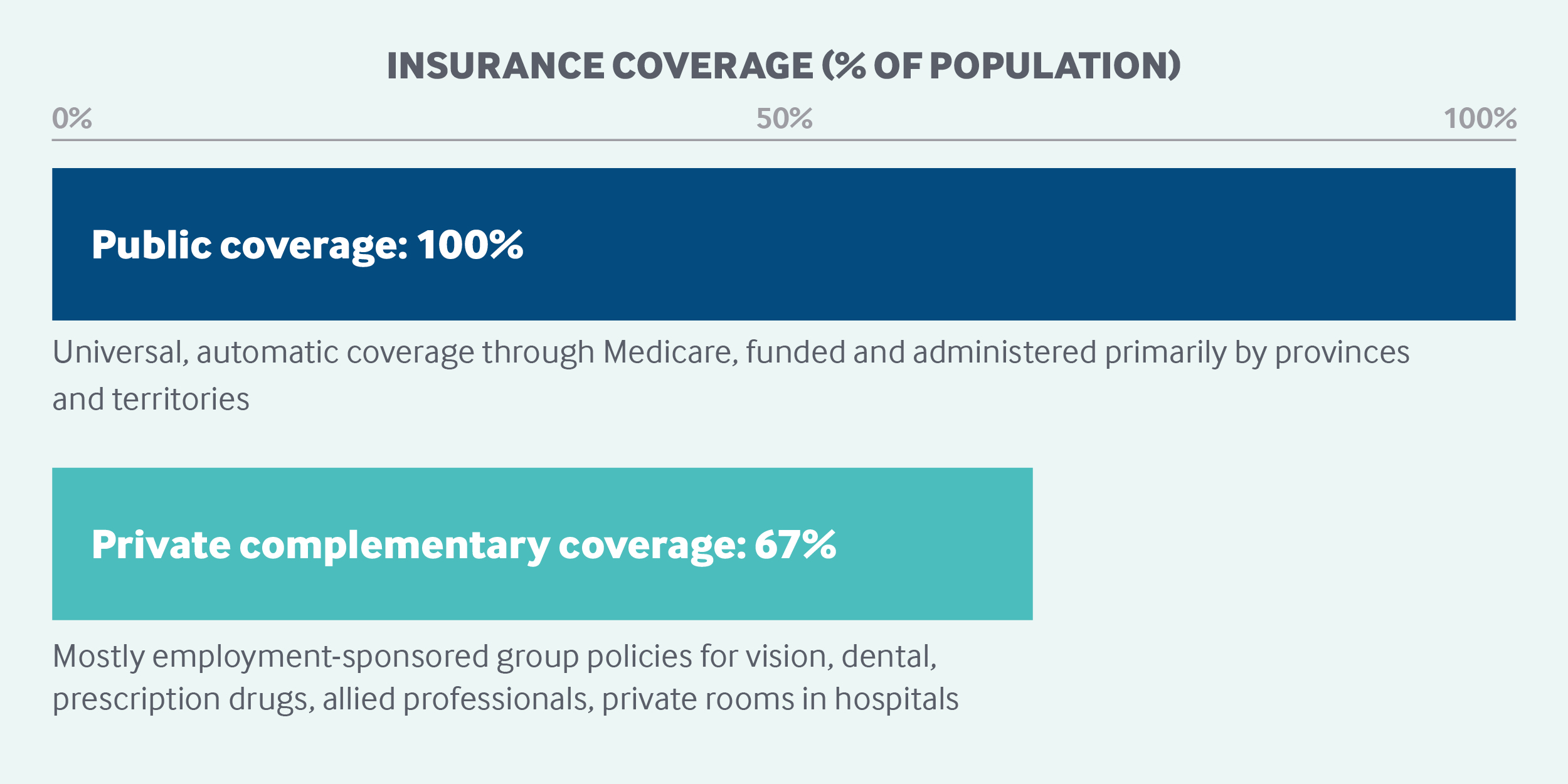

Canada has a decentralized, universal, publicly funded health system called Canadian Medicare. Health care is funded and administered primarily by the country’s 13 provinces and territories. Each has its own insurance plan, and each receives cash assistance from the federal government on a per-capita basis. Benefits and delivery approaches vary. All citizens and permanent residents, however, receive medically necessary hospital and physician services free at the point of use. To pay for excluded services, including outpatient prescription drugs and dental care, provinces and territories provide some coverage for targeted groups. In addition, about two-thirds of Canadians have private insurance.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

Canadian Medicare — Canada’s universal, publicly funded health care system — was established through federal legislation originally passed in 1957 and in 1966. The Canada Health Act of 1984 replaces and consolidates the two previous acts and sets national standards for medically necessary hospital, diagnostic, and physician services. To be eligible to receive full federal cash contributions for health care, each provincial and territorial (P/T) health insurance plan needs to comply with the five pillars of the Canada Health Act, which stipulate that it be:

- Publicly administered

- Comprehensive in coverage conditions

- Universal

- Portable across provinces

- Accessible (for example, without user fees).

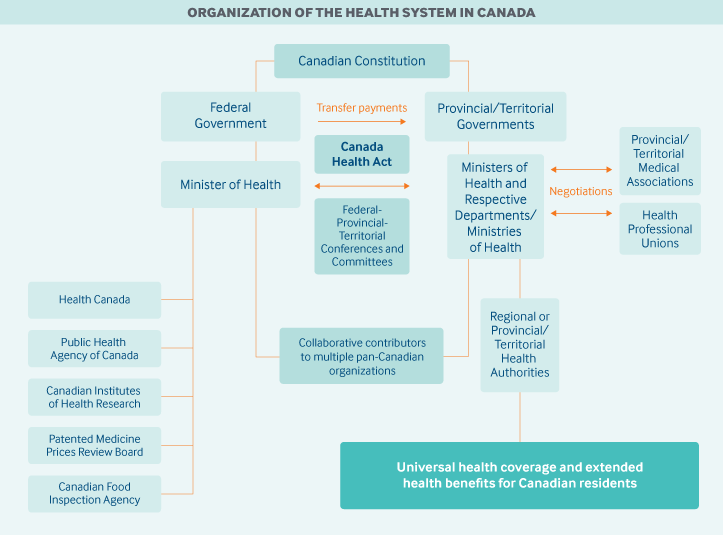

Role of government: Canadian P/T governments have primary responsibility for financing, organizing, and delivering health services and supervising providers. The jurisdictions directly fund physicians and drug programs, and contract with delegated health authorities (either a single provincial authority or multiple subprovincial, regional authorities) to deliver hospital, community, and long-term care, as well as mental and public health services.

The federal government cofinances P/T universal health insurance programs and administers a range of services for certain populations, including eligible First Nations and Inuit peoples, members of the Canadian Armed Forces, veterans, resettled refugees and some refugee claimants, and inmates in federal penitentiaries. It also regulates the safety and efficacy of medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and natural health products, funds health research and some information technology systems, and administers several public health functions on a national scale.

At the national level, a variety of governmental agencies oversee specific functions:

- Health Canada, which is the federal ministry of health, plays a key regulatory role in food and drug safety, medical device and technology review, and the upholding of national standards for universal health coverage.

- The Public Health Agency of Canada is responsible for public health, emergency preparedness and response, infectious and chronic disease control and prevention, and health promotion.

- A new federal government department, Indigenous Services Canada, funds certain health services for First Nations and Inuit.

Most providers are self-governing under P/T law; they are registered with a provincial regulatory body (such as the College of Physicians and Surgeons) that ensures that education, training, and quality-of-care standards are met.

Most provinces have an ombudsperson who advocates on behalf of patients.

Role of public health insurance: Total health spending is estimated to have reached 11.5 percent of GDP in 2017; the public sector and private sector accounted for approximately 70 percent and 30 percent of total health expenditures, respectively.1 Each P/T health insurance plan covers all medically necessary hospital and physician services (on a prepaid basis). Supplementary services, or those not covered under Canadian Medicare, are largely privately financed, either from patient out-of-pocket payments or through employer-based or private insurance.

Provinces and territories cover all of their own residents in accordance with their respective residency requirements.2 Temporary legal visitors, undocumented immigrants, visitors who stay in Canada beyond the duration of a legal permit, and those who enter the country illegally are not covered by any federal or P/T program. Provinces and territories provide limited emergency services to these populations — no physician or hospital can refuse to provide care in an emergency, and midwives provide some maternity services.3

The main funding source is general P/T government revenue. Most P/T revenue comes from taxation. About 24 percent (an estimated CAD 37 billion, or USD 29.4 billion, in 2017–2018) is provided by the Canada Health Transfer, the federal program that funds health care for provinces and territories.4

Role of private health insurance: Private insurance, held by about two-thirds of Canadians, covers services excluded under universal health coverage, such as vision and dental care, outpatient prescription drugs, rehabilitation services, and private hospital rooms. In 2015, approximately 90 percent of premiums for private health plans were paid through employers, unions, or other organizations under a group contract or uninsured contract (by which a plan sponsor provides benefits to a group outside of an insurance contract). In 2017, private insurance was estimated to account for 12 percent of total health spending. 5 The majority of insurers are for-profit.6

Services covered: To qualify for federal financial contributions, P/T insurance plans must provide first-dollar coverage of medically necessary physician, diagnostic, and hospital services (including inpatient prescription drugs) for all eligible residents. All P/T governments also provide public health and prevention services (including immunizations) as part of their public programs.

However, there is no nationally defined statutory benefit package; most public coverage decisions are made by P/T governments in conjunction with the medical profession. Because of this, coverage varies across P/T insurance plans for services not federally mandated as medically necessary, including outpatient prescription drugs, mental health care, vision care, dental care, home care, midwifery services, medical equipment, and hospice care.

Most provinces have public prescription drug coverage programs for specific populations, such as recipients of social assistance, seniors aged 65 and older, and children and youth. Some programs charge premiums, often income-related.7

There are some health services that, for the most part, are not covered by any P/T insurance plan, including dental services, physiotherapy, psychologist visits, chiropractic care, and cosmetic or plastic surgery.

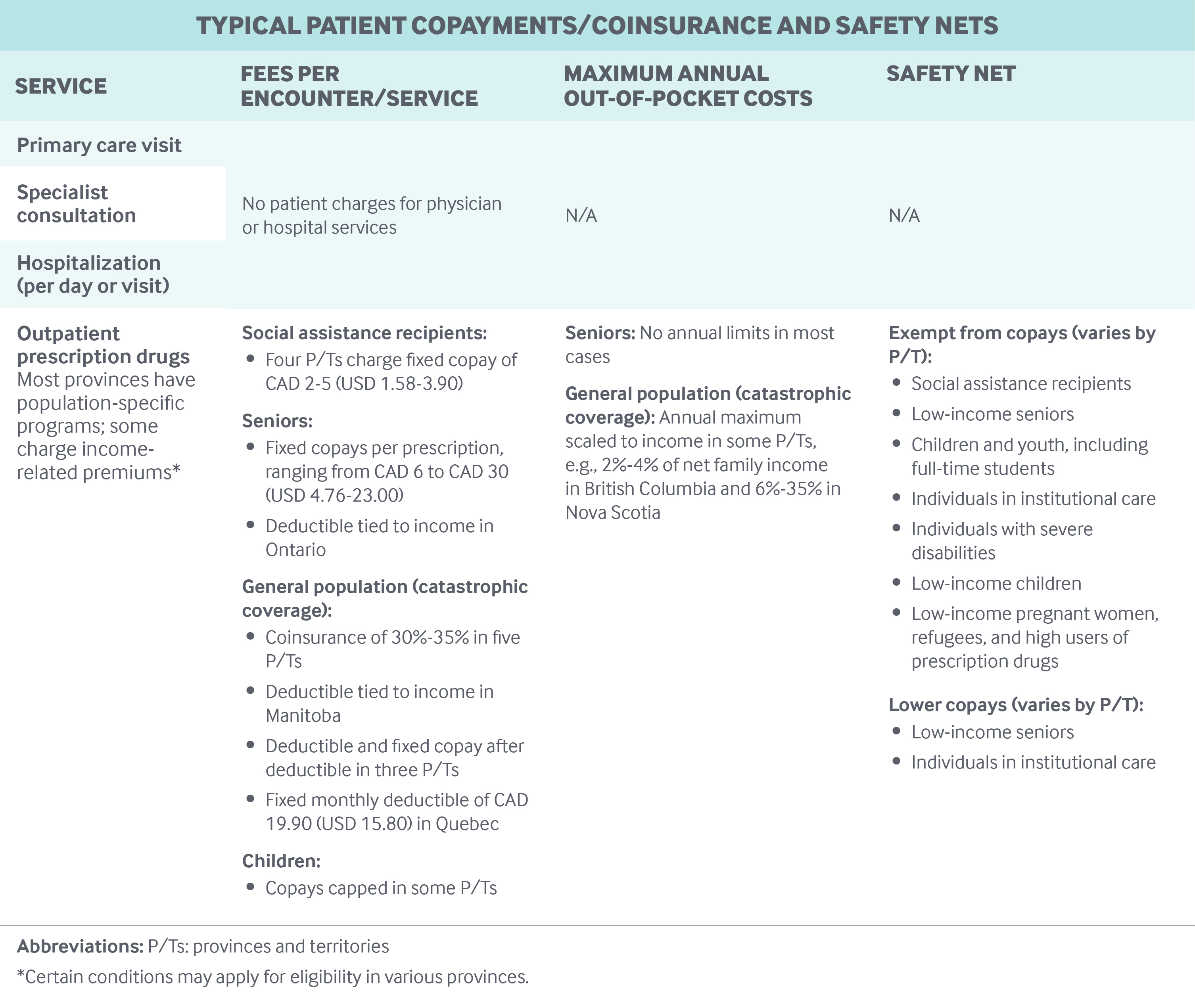

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: There is no cost-sharing for publicly insured physician, diagnostic, and hospital services. Physicians are not allowed to charge patients prices above the negotiated fee schedule.

In 2016, out-of-pocket payments were estimated to represent about 15 percent of total health spending; the majority was spent on nonhospital institutions (mainly long-term care homes), prescription drugs, dental care, and vision care.8

Safety nets: To help cover needed prescriptions, provinces and territories provide outpatient drug plans to some individuals lacking private employer-sponsored insurance. Most P/T outpatient drug plans operate as payers of last resort, targeting people on social assistance or of retirement age. These plans vary considerably. For instance, Quebec administers a universal drug plan by mandating that eligible individuals have private coverage and enrolls those not eligible for private coverage in the public plan. In contrast, Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, administers a universal prescription drug program for seniors, children and youth without private coverage, and recipients of social assistance.

P/T governments also provide some relief for people with high out-of-pocket expenses. After citizens pay more than 3 percent of their net income, or CAD 2,288 (USD 1,816), whichever is less, for eligible medical expenses per year, they can receive a 15 percent tax credit for any remaining expenses.9

In addition, provinces and territories pay for accommodation and food expenses (beyond nursing care) of indigent individuals in publicly financed long-term care facilities.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Students who obtained a medical degree from one of Canada’s 17 public medical schools paid an average annual tuition of CAD 14,780 (USD 11,730) in 2018–2019.10 About 27 percent of Canada’s physicians received their degree outside Canada.11

In 2017, 92 percent of physicians practiced in urban locations.12 There are no national programs to ensure a supply of doctors in rural and remote locations. However, most provinces have rural practice initiatives. For example, Alberta’s Rural, Remote, Northern Program guarantees physicians an income greater than CAD 50,000 (USD 39,382).13

Primary care: In 2017, there were 2.3 practicing physicians per 1,000 population; about half (1.2 per 1,000 population) were family physicians, or general practitioners (GPs), and the rest specialists (1.15 per 1,000 population).14 GPs act largely as gatekeepers, and many provinces pay lower fees to specialists for non-referred consultations.

Most physicians are self-employed in private practices. In 2014, the last year of the National Physician Survey, about 46 percent of GPs worked in a group practice, 19 percent in an interprofessional practice, and 15 percent in a solo practice.15 In several provinces, networks of GPs work together and share resources, with variations across provinces in the composition and size of teams.16

In 2017, about 62 percent of regulated nurses (registered nurses, nurse practitioners, and licensed practical nurses) worked in hospitals and 15 percent in community health settings on salaries.17 In the three northern territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut), primary care is often nurse-led.

In theory, patients have free choice of a GP; in practice, however, patients may not be accepted into a physician’s practice if the physician has a closed list. The requirements for patient registration vary considerably by province and territory, but no jurisdiction has implemented strict rostering.18 Quebec, through Family Medicine Groups, has used patient enrollment and added (human and financial) resources to improve access to care.

Fee-for-service is the primary form of physician payment, although there has been a movement toward alternative forms of payment, such as capitation. In 2016–2017, fee-for-service payments made up about 45 percent of GP payments in Ontario, 72 percent in Quebec, and 82 percent in British Columbia; capitation and, to a lesser extent, salaries made up remaining payments.19

In 2016–2017, the average clinical payment was CAD 276,761 (USD 219,651) for family medicine, CAD 357,264 (USD 283,543) for medical specialties, and CAD 477,406 (USD 378,894) for surgical specialties.20 In most provinces, specialists have the same fee schedule as primary care physicians.

Provincial ministries of health negotiate physician fee schedules (for primary and specialist care) with medical associations. In some provinces, such as British Columbia and Ontario, payment incentives have been linked to performance.

Outpatient specialist care: Specialists are mostly self-employed. There are few formal multispecialty clinics.

The majority of specialist care is provided in hospitals, on both an inpatient and an outpatient basis, although there is a trend toward providing less-complex services in nonhospital diagnostic or surgical facilities.

Specialists are paid mostly on a fee-for-service basis, although there is variation across provinces. For example, in Quebec, alternative payment structures made up about 15 percent of total payments to specialists in 2016–2017, as compared to 22 percent in British Columbia and 33 percent in Saskatchewan.

Patients can choose to go directly to a specialist, but it is more common for GPs to refer patients to specialty care. Specialists who bill P/T public insurance plans are not permitted to receive payment from privately insured patients for services that would be covered under public insurance.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: The majority of physicians and specialists bill P/T governments directly, although some are paid a salary by a hospital or facility. Patients may be required to pay out-of-pocket for services that are not covered by public insurance plans.

After-hours care: After-hours care is often provided in physician-led walk-in clinics and hospital emergency rooms. In most provinces and territories, a free telephone service allows citizens to get health advice from a registered nurse 24 hours a day.

Historically, GPs have not been required to provide after-hours care, although newer group-practice arrangements stipulate requirements or financial incentives for providing after-hours care to registered patients.21 In 2015, 48 percent of GPs in Canada (67% in Ontario) reported having arrangements for patients to see a doctor or nurse after hours.22 Yet, in 2016, only 34 percent of patients reported having access to after-hours care through their GP.23

Hospitals: Hospitals are a mix of public and private, predominantly not-for-profit, organizations. They are often managed by delegated health authorities or hospital boards representing the community. In most provinces and territories, many hospitals are publicly owned,24 whereas in Ontario they are predominantly private not-for-profit corporations.25

There are no specific data on the number of private for-profit clinics (primarily diagnostic and surgical). However, a 2017 survey identified 136 private for-profit clinics across Canada.26

Hospitals in Canada generally operate under annual global budgets, negotiated with the provincial ministry of health or delegated health authority. However, several provinces, including Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia, have considered introducing activity-based funding for hospitals, paying a fixed amount for some services provided to patients.27

Hospital-based physicians generally are not hospital employees and are paid fee-for-service directly by the provincial ministries of health.

Mental health care: Physician-provided mental health care is covered under Canadian Medicare, in addition to a fragmented system of allied services. Hospital-based mental health care is provided in specialty psychiatric hospitals and in general hospitals with mental health beds. The P/T governments all provide a range of community mental health and addiction services, including case management, help for families and caregivers, community-based crisis services, and supportive housing.28

Private psychologists are paid out-of-pocket or through private insurance. Psychologists who work in publicly funded organizations receive a salary.

Mental health has not been formally integrated into primary care. However, some organizations and provinces have launched efforts to coordinate or collocate mental health services with primary care. For instance, in Ontario, an intersectoral mental health strategy has been in place since 2011 and was expanded in 2014 to better integrate mental health and primary care.29

Long-term care and social supports: Long-term care and end-of-life care provided in nonhospital facilities and in the community are not considered insured services under the Canada Health Act. All P/T governments fund such services through general taxation, but coverage varies across jurisdictions. All provinces provide some residential care and some combination of case management and nursing care for home care clients, but there is considerable variation when it comes to other services, including medical equipment, supplies, and home support. Many jurisdictions require copayments.

Eligibility for home and residential long-term care services is generally determined via a needs assessment based on health status and functional impairment. Some jurisdictions also include means-testing. About half of P/T governments provide some home care without means-testing, but access may depend both on assessed priority and on the availability of services within capped budgets.30

The government funds personal and nursing care in residential long-term facilities. In addition, financial supplements based on ability to pay can help support room-and-board costs. Some provinces have established minimum residency periods as an eligibility condition for facility admission.

Spending on nonhospital institutions, most of which are residential long-term care facilities, was estimated to account for just over 11 percent of total health expenditures in 2017, with financing mostly from public sources (70%).31 A roughly equal mix of private for-profit, private nonprofit, and public facilities provide facility-based long-term care.

Public funding of home care is provided either through P/T government contracts with agencies that deliver services or through government stipends to patients to purchase their own services. For example, British Columbia’s Support for Independent Living program allows clients to purchase their own home-support services.32

Provinces and territories are responsible for delivering palliative and end-of-life care in hospitals (covered under Canadian Medicare), where the majority of such costs occur. But many provide some coverage for services outside those settings, such as physician and nursing services and drug coverage in hospices, in nursing facilities, and at home.

In June 2016, the federal government introduced legislation that amended the criminal code to allow eligible adults to request medical assistance in dying from a physician or nurse practitioner. Since that time, P/T governments and medical associations have set up processes and regulatory frameworks to allow for medical assistance in dying for individuals facing terminal or irreversible illnesses.

More than 8 million Canadians are estimated to have provided unpaid support to persons living with chronic health and social needs in 2012.33 Support for informal caregivers (estimated to provide 66% to 84% of care to the elderly) varies by province and territory.34 For example, Nova Scotia's Caregiver Benefit Program offers eligible caregivers and care recipients CAD 400 (USD 317) per month.35 There are also some federal programs, including the Canada Caregiver Credit and the Employment Insurance Compassionate Care Benefit.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

Many provinces have agencies responsible for producing health care system reports and for monitoring system performance. In addition, the Canadian Institute for Health Information produces regular public reports on health system performance, including indicators of hospital and long-term care facility performance. To date, there is no information publicly available on doctors’ performance across the country. Most provinces post summary inspection reports online.

Home care agencies do not have reporting standards similar to those for residential long-term care. The Canadian Institute for Health Information has the Home Care Reporting System, which contains demographic, clinical, functional, and resource utilization data for clients served by publicly funded programs across Canada. However, in 2018, only eight jurisdictions were submitting data.36

The use of financial incentives to improve quality is limited. At the physician level, they have had, to date, little demonstrable effect on quality.37 Professional revalidation requirements for physicians, including those for continuing education and peer review, vary across provinces.

A variety of other quality initiatives are in progress:

- The federally funded Canadian Patient Safety Institute promotes best practices and develops strategies, standards, and tools.

- Provincial quality councils facilitate process improvements to produce higher-quality health care.

- The Optimal Use Projects program, operated by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, provides recommendations (though not formal clinical guidelines) to providers and consumers to encourage the appropriate prescribing, purchasing, and use of medications.

- The federally funded Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement works with P/T governments to implement performance improvement initiatives.

- Accreditation Canada — a nongovernmental organization — provides voluntary accreditation services to about 1,200 health care organizations across Canada, including regional health authorities, hospitals, long-term care facilities, and community organizations.

- Provincial cancer registries feed data to the Canadian Cancer Registry, a national administrative survey that tracks cancer incidence.

- There is no national patient survey, although a standardized acute-care hospital inpatient survey developed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information has been implemented in several provinces. Each province has its own strategies and programs to address chronic disease.

- The P/T premiers, or prime ministers, established the Health Care Innovation Work Group in 2012 to improve quality by, for example, promoting guidelines for treating heart disease and diabetes and reducing costs.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

The Public Health Agency of Canada includes health disparities reporting in its mandate, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information also reports on disparities in health care and health outcomes, with a focus on lower-income Canadians.38 No formal or periodic process exists to measure disparities; however, several P/T governments have departments and agencies devoted to addressing population health and health inequities.

Health disparities between indigenous and nonindigenous Canadians are a concern for government at both the federal and the P/T level. The 2018 federal budget offers new funding of CAD 5 billion (USD 3.9 billion) for indigenous people, building on previous investments totaling CAD 11.8 billion (USD 9.3 billion). The money is earmarked for education, the environment (for example, water quality), and health and social services.39

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established to collect stories regarding the events and effects of the Indian Residential School legacy, released a series of calls to action, including several addressing health disparities that affect indigenous communities.40

In Ontario, a strategy to improve the health of indigenous people was launched in 2016, with emphasis on investments in primary care, cultural competency training for health care providers, access to fresh fruit and vegetables, and mental health services for First Nations youth.41

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

Provinces and territories have introduced several initiatives to improve the integration and coordination of care for chronically ill patients with complex needs. These include Divisions of Family Practice (British Columbia), Family Medicine Groups (Quebec), the Regulated Health Professions Network (Nova Scotia), and Health Links (Ontario).

In addition, Ontario has long-standing community-based and multidisciplinary primary care models in place, including Community Health Centres and Aboriginal Health Access Centres. Ontario also continues to expand a pilot program that bundles payments across different providers. This alternative payment approach is expected to improve care coordination for patients as they transition from hospital to the community.42

What is the status of electronic health records?

Uptake of health information technologies has been slowly increasing in recent years. Provinces and territories are responsible for developing their own electronic information systems, with national funding and support through Canada Health Infoway. However, there is no national strategy for implementing electronic health records and no national patient identifier.

According to Canada Health Infoway, provinces have systems for collecting data electronically for the majority of their populations; however, interoperability is limited. In 2017, 85 percent of GPs reported using electronic medical records, but patients have limited access to their own electronic health information.43

How are costs contained?

Costs are controlled principally through single-payer purchasing, and increases in real spending mainly reflect government investment decisions or budgetary overruns. Cost-control measures include:

- Mandatory global budgets for hospitals and regional health authorities

- Negotiated fee schedules for providers

- Drug formularies for provincial drug plans

- Resource restrictions for physicians and nurses (such as provincial quotas for students admitted annually)

- Restrictions on new investment in capital and technology.

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health oversees the national health technology assessment process, which is one mechanism for containing new technology costs. This agency produces information about t clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and broader impact of drugs, medical technologies, and health systems. The agency’s Common Drug Review assesses the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of drugs and provides common, nonbinding formulary recommendations to the publicly funded provincial drug plans (except in Quebec) to support greater consistency in access and evidence-based resource allocation.

The federal Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, an independent, quasi-judicial body, regulates the introductory prices of new patented medications. The board regulates factory gate prices but does not have jurisdiction over wholesale or pharmacy prices, or over pharmacists’ professional fees.

Since 2010, the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance has negotiated lower prices for 95 brand-name medications and has set price limits at 18 percent of equivalent brand-name drug prices for the 15 most common generics.44 Notwithstanding this pan-Canadian collaboration, jurisdiction over prices of generics and control over pricing and purchasing under public drug plans (and, in some cases, pricing under private plans) are held by provinces, leading to some interprovincial variation.

In addition, the Choosing Wisely Canada campaign provides recommendations to governments, providers, and the public on reducing low-value care.45

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

As noted above, prescription drugs, outside of hospitals, are not universally covered. At the federal level, there are signs of renewed interest in a pan-Canadian system of drug coverage. In 2018, the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare was established, and an interim report was produced in 2019.46 If a national program moves forward, it will be the biggest expansion of public funding and coverage since Canadian Medicare was introduced.

Provinces and territories continue to implement structural reforms to improve efficiency. The latest example occurred in 2017 when Saskatchewan replaced its 12 regional health authorities with a single provincial health authority. This initiative reflects a national trend toward greater administrative centralization. Similarly, as part of an evolving reform effort, Manitoba established a single provincial organization — Shared Health — to centralize some clinical and administrative services. In 2019, the Ontario government announced its plans to consolidate several provincial arm’s-length agencies, along with the 14 subprovincial health authorities — Local Health Integration Networks — that administer and deliver health care for their local populations, into a single provincial agency.47