By Andrea Donatini, Emilia-Romagna Regional Health Authority

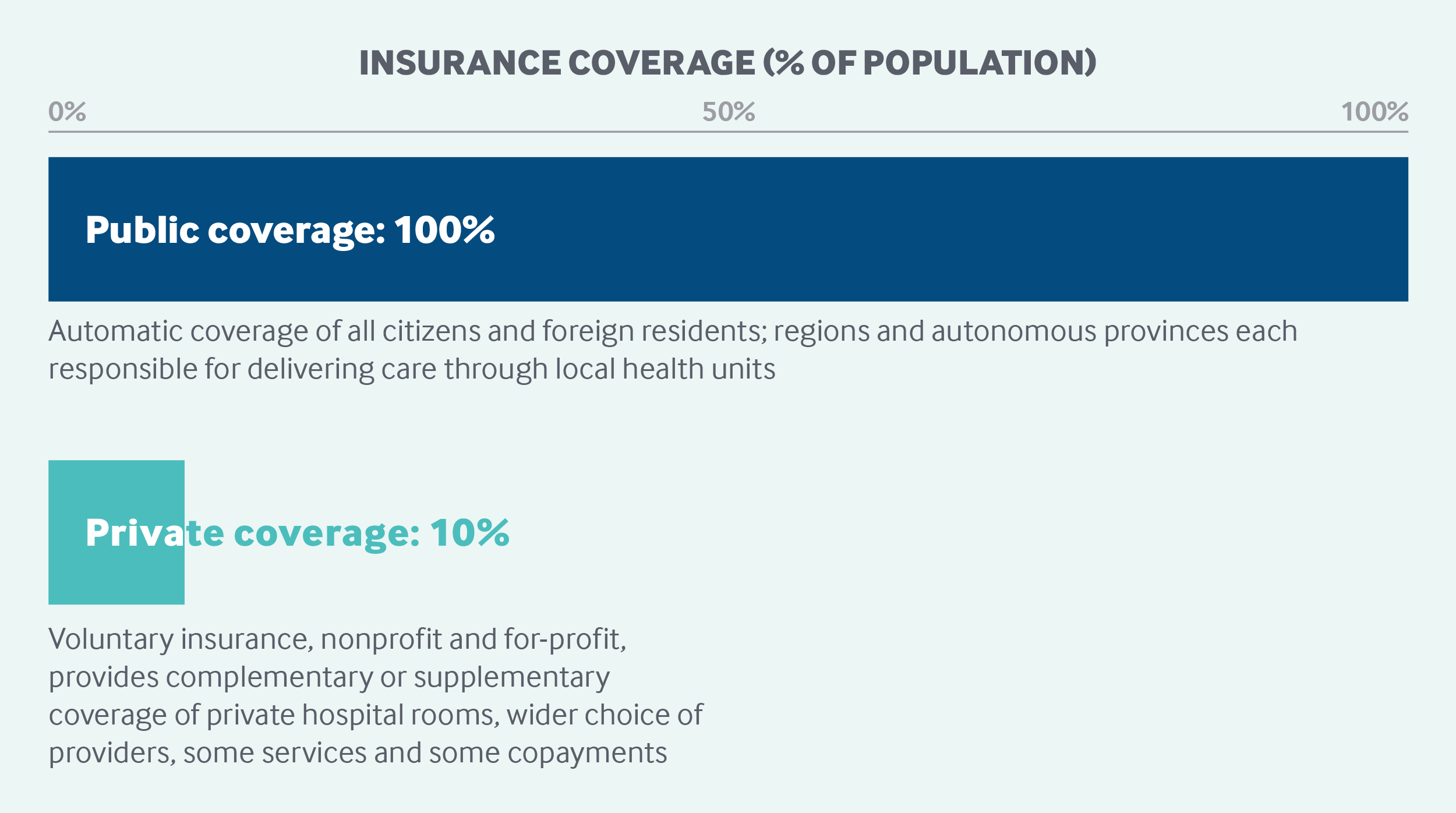

Italy’s National Health Service automatically covers all citizens and legal foreign residents. It is funded by corporate and value-added tax revenues collected by the central government and distributed to the regional governments, which are responsible for delivering care. Residents receive mostly free primary care, inpatient care, and health screenings. Other statutory benefits include maternity care, specialty care, home care, hospice care, preventive medicine, and pharmaceuticals. Patients make copayments for specialty visits and procedures and some outpatient drugs. Exempt from cost-sharing are pregnant women, patients with HIV or other chronic diseases, and young children and older adults in lower-income households. There are no deductibles for residents. Private health insurance has a limited role in Italy’s health coverage system.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

Universal coverage is provided through Italy’s National Health Service (Servizio sanitario nazionale, or SSN), established through legislation in 1978. The SSN automatically covers all citizens and legal foreign residents. Since 1998, undocumented immigrants have had access to urgent and essential services. Temporary visitors are responsible for the costs of any health services they receive.

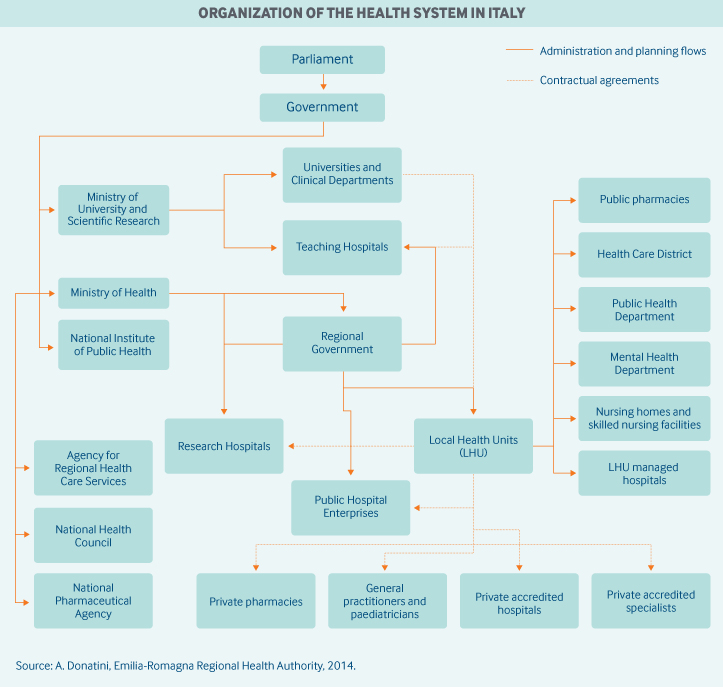

Role of government: The organization and delivery of health services is decentralized. Nineteen regions and two autonomous provinces are responsible for delivering care through 100 local health units, which deliver primary care, hospital care, outpatient specialist care, public health care, and health services related to social care. Regions enjoy significant autonomy in determining the macro structure of their health systems. The local health units each have a general manager, who is appointed by the regional governor.

As specified in Italy’s constitution, national health policies and priorities are a responsibility of the central government. The central government also determines annual SSN funding and controls the allocation of resources to each region. Health agencies and ministries include the following:

- The Ministry of Health, which oversees health care planning (such as determining the essential benefits package), health system ethics, the supply of health professionals, information systems, and other areas

- The National Committee for Medical Devices, which develops cost-benefit analyses and determines reference prices for medical devices

- The Agency for Regional Health Services, the sole institution responsible for conducting comparative-effectiveness analyses, which is accountable to the regions and to the Ministry of Health

- The National Pharmaceutical Agency, which governs prescription drug pricing, reimbursement policies, and all other matters related to the pharmaceutical industry.1

Role of public health insurance: Public financing accounted for 74.2 percent of total health spending in 2018, with total expenditures standing at 8.8 percent of GDP.2 The public system is financed primarily through two mechanisms3:

- A corporate tax (approximately 18.6% of 2018 total funding), which is pooled nationally and allocated back to the regions. Corporate tax allocations are typically in proportion to a region’s contributions. There are large interregional variations in the corporate tax base, resulting in inequalities in financing.

- A fixed proportion of the national value-added tax revenue (approximately 60% of 2018 total funding) collected by the central government, which is redistributed to regions with insufficient resources to provide essential services.

The regions are allowed to generate their own additional revenue, leading to further interregional financing differences.

Local health units are funded mainly through capitated budgets.

Role of private health insurance: Since the SSN does not allow people to opt out of the system and seek only private care, substitutive insurance does not exist. But complementary and supplementary private health insurance play a limited role in the health system, accounting for roughly 1 percent of total spending in 2014.

Approximately 10 percent of the population have some form of voluntary health insurance, which covers services excluded under SSN essential benefits, offers a higher standard of comfort and privacy in hospital facilities, and affords wider choice among public and private providers. Some private health insurance policies also cover copayments for privately provided services or a daily rate of compensation during hospitalization.4 Tax benefits favor complementary insurance (insurance for copayments) over supplementary voluntary insurance (which covers the cost of health care services not included in the essential benefits package).

There are two types of private health insurance: corporate, for which companies cover employees and sometimes their families, and noncorporate, with individuals buying insurance for themselves or their families. Policies, either collective or individual, are supplied by for-profit and nonprofit organizations. The market comprises voluntary mutual insurance organizations and corporate and collective funds organized by employers or professional associations for their employees or members. Nonprofit organizations cover the majority of the insured.5

Services covered: The central government defines a national statutory benefits package offered to all residents in every region: the LEA (Livelli essenziali di assistenza). Covered benefits include:

- pharmaceuticals

- inpatient care

- preventive medicine

- outpatient specialist care

- maternity care

- home care

- primary care

- hospice care.

Durable medical equipment, long-term care, and other selected services are covered only for patients with certain medical conditions.

Regions can offer services not included in the national statutory benefits but must finance those services themselves.

Prescription drugs are divided into three tiers according to clinical effectiveness and, in part, cost-effectiveness:

- Tier 1 (Classe A) includes lifesaving drugs and treatments for chronic conditions and is covered in all cases.

- Tier 2 (Classe C) includes drugs for all other conditions and is not covered by the SSN.

- Tier 3 (Classe H) comprises drugs that can be delivered only in a hospital setting.

The three tiers are updated regularly by the National Pharmaceutical Agency in recognition of new clinical evidence. For some categories of drugs, therapeutic plans are mandated and prescriptions must follow clinical guidelines.

Dental care is generally not covered, except for children through age 16, vulnerable populations, and people in economic and emergency need.

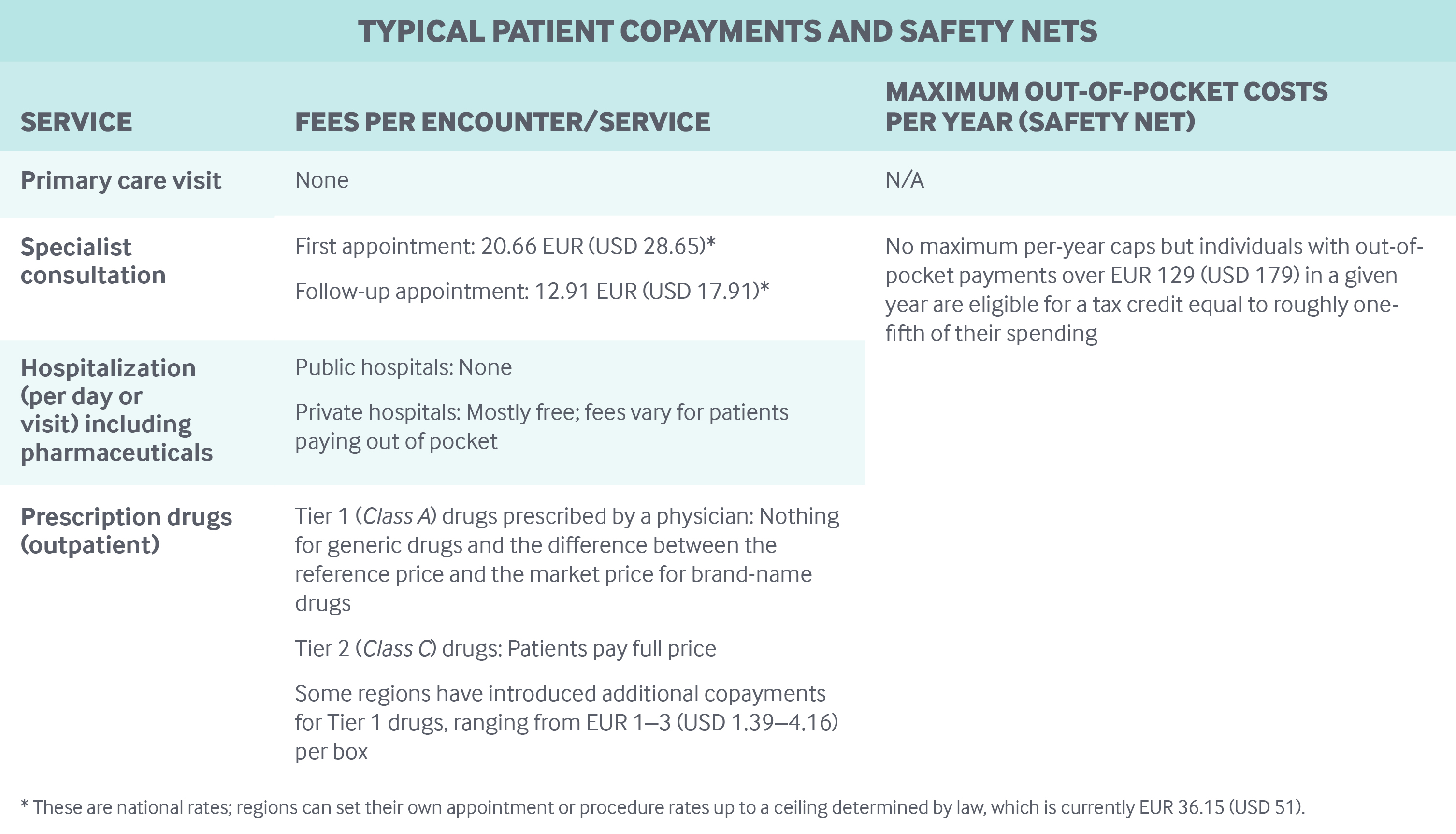

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: Primary and inpatient care are free at the point of use. Most preventive screenings are also provided free of charge.

Procedures and specialist visits can be prescribed either by a general practitioner (GP) or by a specialist. Fees for visits range from EUR 12.91 (USD 17.91) for a follow-up visit) to EUR 20.66 (USD 28.65) for first encounters. Patients also make copayments for each prescribed procedure up to a ceiling determined by law — currently EUR 36.15 (USD 50.14).6

Patients are subject to copayments for some outpatient drugs (see table below). In addition, a EUR 25 (USD 35) copayment has been introduced for the “unnecessary” use of emergency services, but some regions have not enforced this copayment.

No other forms of deductible exist. Public and private providers under a contract with the SSN are not allowed to charge above scheduled fees.

In 2018, an estimated 23 percent of total health spending was paid out-of-pocket, mainly for drugs not covered by the public system and for dental care.7

Safety nets: All individuals with out-of-pocket payments over EUR 129 (USD 181) in a given year are eligible for a tax credit equal to roughly one-fifth of their spending.

Exemptions from cost-sharing are applied to children under age 6 and adults over age 65 who live in households with a gross income below a nationally defined threshold of approximately EUR 36,000 (USD 40,930). People with severe disabilities, as well as prisoners, are exempt from cost-sharing. In addition, people with rare or chronic diseases, including HIV, and pregnant women are exempt from cost-sharing for treatments related to their condition.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Enrollment in university medical education programs (medicine, surgery, and dentistry) is based on a competitive assessment exam. There are also restrictions on advancement to postgraduate levels, where medical school graduates can specialize in fields such as cardiology, neurology, and general surgery. Medical schools are largely public, with yearly fees of approximately EUR 2,200 (USD 2,500). Postgraduate students pay the same fee but also receive a monthly stipend of EUR 1,800 (USD 2,000).

Primary care: Primary care is provided by contracted self-employed and independent GPs and pediatricians. They are paid a capitation fee based on the number of patients on their list.8 Local health units also can pay additional allowances for delivering care to specific patients, such as home care to chronically ill patients; for reaching targets related to quality or spending levels; or for delivering additional patient services.

Capitation is adjusted for patient age, and accounts for approximately 70 percent of a GP’s overall payment. On average, the gross income of a GP ranges between EUR 80,000 (USD 110,957) and EUR 120,000 (USD 166,436), depending on list size. All the costs — for medical tools, office rental, and personnel — are borne by the GP.

GPs and pediatricians willing to work in rural or remote areas receive an additional payment of approximately EUR 5 (USD 6) per patient.

In 2017, there were approximately 52,000 GPs and pediatricians (34% of all practitioners) working for the SSN. In comparison, there were 101,000 hospital clinicians, including specialists (66%).9

Patients are required to register with a gatekeeping GP. They may choose any physician whose list has not reached the maximum number of patients allowed (1,500 for GPs and 800 for pediatricians) and may switch at any time.

The payment levels, duties, and responsibilities of GPs are determined in a collective agreement signed periodically after consultations between the central government and the GPs’ trade unions. In addition, regions and local health units can sign contracts covering additional services.

GPs are not allowed to bill patients for any procedure delivered, although they are allowed to deliver treatments in a private setting provided they do not dedicate more than five hours per week to private care. If GPs decide to deliver private care for more than five hours per week, they must accept a reduction in their maximum number of patients (48 patients per additional hour).

In recent years, group practices have become more widespread, particularly in the northern part of the country. GPs and pediatricians who participate in some type of group practice — and ideally share offices and patient health record systems — receive additional payments per patient. They also receive additional payments for employing a nurse or secretary. In 2017, nearly 71 percent of GPs and 65 percent of pediatricians were working in a team.9 Group practices typically include from three to eight GPs.

To further coordinate meeting all the health needs of their populations, some regions are asking GPs to work in multidisciplinary groups composed of specialists, nurses, and social workers. This arrangement is encouraged by additional payments to GPs per patient and by supplying teams with needed personnel.

Outpatient specialist care: Outpatient specialist care is generally provided by local health units or by public and private accredited hospitals under contract with them. Once referred, patients can choose any public or private accredited hospital but are not given a choice of specialist. Payment rates for outpatient specialist care are determined by each region, with national averages serving as a reference.

Outpatient specialist visits are generally provided by self-employed specialists working under contract with the SSN. They are paid an hourly fee negotiated nationally between the government and the trade unions; the current rate is approximately EUR 32 (USD 44). Outpatient specialists seeing public patients cannot bill above the fee schedule, but can see private patients without any limitations. Specialists employed by local health units and public hospitals can see private patients in public hospitals by allotting a portion of their extra income to the hospital.

Multispecialty groups are more common in northern regions of the country.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Patient copayments are limited to outpatient specialist visits and diagnostic testing, while primary care visits are provided free of charge. Copayments are usually paid by the patient before the visit or test.

After-hours care: After-hours emergency care is the responsibility of local health units, which provide emergency medical services (Guardia medica) staffed by continuous-care physicians. The hourly rate, negotiated between the GP trade unions and the government, is approximately EUR 25 (USD 35). After examining patients and providing any initial treatment, the doctors can prescribe medications, issue employees’ medical certificates, and recommend hospital admission. The service normally operates at night and on weekends.

Primary care doctors are not required to provide after-hours care, but many are open until 8 p.m. There is no national or regional medical telephone advice line.

Information on a patient’s after-hours visit is not routinely sent to the patient’s GP. To improve accessibility, government and GP associations are trying to promote a model in which GPs, specialists, and nurses coordinate to ensure 24-hour access and avoid unnecessary use of hospital emergency departments. Implementation is uneven across regions.

Hospitals: Public funds are allocated by local health units to public and accredited private hospitals (for-profit and nonprofit). In 2017, there were approximately 165,000 beds in public hospitals and 44,000 in private accredited hospitals.9 Public hospitals either are managed directly by the local health units or operate as semi-independent public enterprises.

A diagnosis-related group–based prospective payment system operates across the country and accounts for most hospital revenue. (However, hospitals run directly by local health units typically have global budgets.) Rates include all hospital expenses, including physician salaries, and costs for expensive technologies and medicines. Teaching hospitals receive additional payments — typically 8 percent to 10 percent of overall revenue — to cover extra costs related to teaching.

There are considerable interregional variations in the prospective payment system, such as how fees are set, which services are excluded, and what tools are employed to influence patterns of care. However, all regions have mechanisms for cutting fees once a spending threshold is reached. In all regions, a portion of funding is administered outside the prospective payment system, such as funding of specific functions like emergency departments and teaching programs.

Hospital-based physicians are salaried employees with an average gross income of EUR 106,000 (USD 147,018). Public-hospital physicians are prohibited from treating patients in private hospitals; all public physicians who see private patients in public hospitals pay a portion of their extra income to the hospital.

In April 2015, the Ministry of Health approved a decree for the reorganization of hospital care. The decree classified public hospitals into three groups, based on population size, service intensity, and scope: base, first-level, and second-level.

Mental health care: Mental health care is provided by the National Health Service in a variety of community-based, publicly funded settings, including community mental health centers, community psychiatric diagnostic centers, general hospital inpatient wards, and residential and semiresidential facilities. In 2017, there were about 2,000 residential facilities and 870 semiresidential facilities.9

The promotion and coordination of mental health care are the responsibility of mental health departments in local health units. Multidisciplinary teams include psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, educators, occupational therapists, people with training in psycho-social rehabilitation, and secretarial staff.

In most cases, primary care does not play a role in the provision of mental health care; a few regions have experimented with assigning responsibility for low-complexity cases (mild depression) to GPs.10

Long-term care and social supports: In Italy, home care, residential care, and semiresidential long-term care are covered by the SSN, with delivery of care organized by local health units. All patients are eligible; admission is based on clinical criteria only.

There has been a significant shift of long-term care from institutions to the communities and an emphasis on home care. Patients with long-term care needs receive predominantly home care (approximately 1 million cases in 2017), with fewer patients receiving care in residential facilities (approximately 278,000 beds in 2017) or semiresidential facilities (16,000 beds).9

Residential and semiresidential facilities provide nurses, physicians, specialist care, rehabilitation services, medical therapies, and devices. Patients must be referred in order to receive residential care. Cost-sharing for residential services varies widely by region but is generally determined by patients’ income. Residential facilities are managed by a mixture of public and private, for-profit and nonprofit organizations.

Community home care is not designed to provide physical or mental health care services but to provide additional assistance during a treatment or therapy. Community home care networks use integrated care teams of nurses, GPs, and specialist physicians to ensure that patient needs are met and families are involved. Community home care is funded publicly.

In spite of government provisions for residential and home care services, long-term care in Italy has traditionally been characterized by a lower degree of public financing and provision than what is found in other European countries. Patients do not receive individual budgets. In addition, no financial support is provided for caregivers, although Italian legislation allows caregivers three days off work per month to look after relatives in need.

Financial assistance for long-term care patients and for their caregivers can take two forms:

- Accompanying allowance: Awarded by the National Pension Institute to all Italian citizens who need continuous assistance. The allowance, which is related to need but not to income or age, amounts to approximately EUR 500 (USD 693) per month. It can be used to buy any type of service.

- Care vouchers: Awarded by municipalities on the basis of income, need, and clinical severity. Only some municipalities currently offer these vouchers. The amount ranges between EUR 300 and EUR 600 (USD 416 and USD 832) per month.

Voluntary organizations still play a crucial role in the delivery of palliative care. A national policy on palliative care has been in place since the late 1990s and has contributed to an increase in services such as hospices, day care centers, and hospital-based palliative care units. In 2017, there were some 270 hospices, with approximately 3,100 beds. However, regional disparities persist: northern regions care, on average, for 95 patients per 100,000 residents at the end of life, while in central and southern regions the rate is 50 per 100,000.9

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

Government at both the national and the regional level is responsible for upholding quality and for ensuring that services included in the list of essential benefits are provided and that waiting times are monitored. Quality-improvement goals are usually set out in “Pacts for Health” (Patto per la salute) between the regions and the central government that link additional resources to the achievement of goals.

The Ministry of Health’s 2015 decree concerning the reorganization of hospital care introduced, for a few procedures, minimum levels of activity and quality thresholds. Many of the law’s provisions are in the process of being implemented, and the effects have not yet been evaluated. In addition, several regions have introduced programs for prioritizing the delivery of care on the basis of patient severity and clinical appropriateness of services prescribed.11

All health care professionals under contract with the National Health Service must be certified by the central or a regional government, and all SSN staff must participate in compulsory continuing education (150 continuing medical education (CME) credits every three years). The National Commission for Accreditation and Quality of Care is responsible for outlining the criteria used to determine which providers are allowed to provide care on behalf of the SSN and for evaluating regional accreditation models (including private hospitals), which vary considerably across the system.

SSN accreditation hinges on extensive quality criteria, including the appropriateness and timeliness of interventions, health status, and patient satisfaction. It also encompasses management of human and technical resources, consistency of the provider’s activity with regional health planning, and an evaluation of the activities conducted and results achieved. Regions have the freedom to set their own accreditation criteria and procedures, as long as the LEA (essential benefits package), is guaranteed. At present, significant variability exists in regional accreditation policies.

National legislation requires all publicly contracted health care providers (hospitals) to issue a “health service chart” with information on service performance, quality indicators, waiting times, quality assurance strategies, and the process for patient complaints. These charts have also been adopted by the private sector for its accreditation process and must be published annually, although dissemination methods are decided regionally. Most providers disseminate these charts through leaflets and the Internet. Nurses and other medical staff are offered financial performance incentives (linked to manager evaluations but not to publicly reported data).

No national patient surveys exist; however, some regions carry out patient satisfaction surveys on a voluntary basis.

The only public reporting on outcomes is the National Outcomes Program, which calculates and reports yearly on a set of hospital outcomes, such as 30-day mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction and admissions for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions.

The National Plan for Clinical Guidelines, implemented in recent years, has produced guidelines on topics ranging from cardiology to cancer prevention and from the appropriate use of antibiotics to cesarean delivery.

Some regions have introduced disease management programs and are experimenting with chronic-care models. Some are maintaining registries, mainly for cancer and diabetes patients. No national registries exist.

At the national level, no public reporting exists on the performance of nursing homes or home care agencies.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

Italy has no national agency tasked with monitoring disparities; in most cases, the monitoring of inequalities is a responsibility of each region.

Interregional inequity is a long-standing concern to both regional and national policymakers. The less-affluent south trails the north in the number of beds and in the availability of advanced medical equipment, has proportionally fewer public versus private facilities, and has less-developed community care services. This gap in availability is increasing. Income-related disparities in self-reported health status are significant.12

The regions receive a proportion of funding from an equalization fund, Fondo Perequativo Nazionale, which aims to reduce inequalities. Aggregate funding for the regions is set by the Ministry of the Economy and Finance, and the resource allocation mechanism is based on capitation adjusted for demographic characteristics and use of health services by age and sex.

There is no systematic public reporting of health and health access variation, although several public and private institutions occasionally publish reports with analysis of health care variation.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

Integration of health and social care services has recently improved, with a shift of long-term care from institutions to communities and an emphasis on home care.

The regions have chronic-care management programs that deal mainly with high-prevalence conditions, such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, and respiratory conditions. Each program involves different competencies. Some regions are also trying to set up disease management programs based on the chronic-care model, although the degree of organization varies across regions.

The most recent Pact for Health, signed in July 2014, is a significant step toward care integration: all regions must establish Primary Care Complex Units involving GPs, specialists, nurses, and social workers. To further promote the integration and adoption of multidisciplinary teams, medical homes are being encouraged in some regions, such as Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, where there are collectively 113 medical homes currently providing multispecialty care to approximately 2.7 million people.

What is the status of electronic health records?

The New Health Information System (Nuovo sistema informativo sanitario, or NSIS) is being implemented incrementally, with the goal of establishing a universal system of electronic records connecting every level of care. It currently provides information on approximately 85 percent of services included in the LEA. Primary care is not included, but hospital, emergency, outpatient specialist, residential, and palliative care are, as well as pharmaceuticals. The NSIS currently registers administrative information on care delivered, but medical information appears to be more difficult to gather. No unique patient identifier exists at the national level, while in most regions administrative records are linked together using unique patient identifiers generated at the regional level.

Monitoring and implementation of the NSIS has been assigned to a steering committee, which includes representatives of the central government, regions, and professional colleges.

The national contract for primary care physicians and pediatricians requires them to have computerized systems; in addition, GPs working in teams are requested to connect all their computers to provide shared access to patient medical records.

Some regions have developed computerized networks to facilitate communication among physicians, pediatricians, hospitals, and territorial services and to improve continuity of care. These networks allow the automatic transfer of patient registries and information on services provided, prescriptions for specialist visits and diagnostics, and laboratory and radiology test outcomes. Fourteen regions have also developed a personal electronic health record, accessible by patients, that contains all of their medical information, such as outpatient specialty care results, medical prescriptions, and hospital discharge instructions. Twenty-one percent of people in these regions have activated their personal health records.

There is also a shift underway from paper-based to electronic prescriptions. Currently, 86 percent of all prescriptions (for drugs and specialist care) are issued electronically. However, in a few regions, the proportion is below 50 percent, especially with regard to drugs.

How are costs contained?

Containing health care costs is a core concern of the central government, as Italy’s public debt is among the highest of the industrialized nations. Fiscal capacity varies greatly across regions. To meet cost-containment objectives, the central government can impose recovery plans on regions with health care expenditure deficits. These plans identify the tools and measures needed to achieve economic balance, such as revising hospital and diagnostic fees, reducing the number of beds, increasing copayments for pharmaceuticals, and reducing human resources through limited turnover.

All regions have adopted various tools to contain costs. In most cases, these include global budgets for hospital and outpatient care (limited to public-hospital enterprises and the private sector), bulk purchasing for drugs and medical products, and the procurement of services such as laundry, meals, cleaning, and sterilization. Regional governments periodically sign Pacts for Health with the national government that link additional resources to the achievement of health care planning and expenditure goals.

National contracting for personnel payment can in some ways be considered a cost-containment tool: both salaried workers (nurses, physicians, administrative personnel) and primary care physicians are paid in accordance with a national contract, with employers (local health units and public-hospital trusts) having limited flexibility in raising payment levels.

Few regional health technology assessment agencies currently exist, and their primary function is to evaluate individual technologies. Assessments are not mandatory for innovative procedures and devices. However, reference prices for medical devices and pharmaceuticals are set according to cost-effectiveness studies carried out by the National Committee for Medical Devices and the National Drugs Agency. Prices for reimbursable drugs are set in negotiations between the government and the manufacturer using criteria such as comparative cost-effectiveness. Prices for nonreimbursable drugs are set by the market.

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

Because of the regionalization of the health system, most innovations in the delivery of care take place at the regional rather than the national level, with some regions viewed as leaders in innovation.

In 2017, Parliament introduced compulsory vaccinations for all infants and children up to age 16, following an increase in the number of deaths due to infectious diseases (mainly mumps) and the antivaccination movement. Children who do not comply with the prescribed vaccination are not allowed to attend kindergartens, nurseries, and schools.

In January 2017, the government approved an updated version of essential covered benefits, with significant changes in the outpatient specialist services that can be delivered by the National Health Service and a further shift of hospital care into outpatient settings. The government estimates an additional expenditure of EUR 800 million (USD 1.1 billion) per year for this reform.

The author would like to acknowledge Sarah Jane Reed and David Squires as contributing authors to earlier versions of this profile.